Why Ruben Gallego’s Viral Condemnation of the Venezuela War Is Shaking Washington

Fifteen minutes ago, Senator Ruben Gallego, a Marine Corps veteran shaped by the Iraq War, detonated a moral and political bomb online, declaring that the United States is unequivocally wrong for starting a war in Venezuela.

His statement cut deeper than typical partisan outrage because it came from someone who has worn the uniform, carried the consequences of war personally, and understands how quickly official narratives collapse under lived reality.

Gallego’s words spread rapidly because they were blunt, unapologetic, and morally absolute, rejecting the careful hedging that usually defines how elected officials discuss military action and American power abroad.

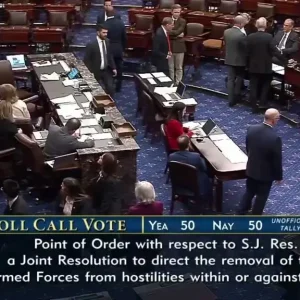

By calling the war illegal, Gallego challenged not only the administration involved, but the broader system that repeatedly allows military action to begin before the public ever hears an honest justification.

The phrase “world cop to world bully” struck a nerve, because it condensed decades of global resentment and domestic exhaustion into a single, shareable indictment of American foreign policy drift.

Supporters argue Gallego voiced what many Americans feel but rarely hear from national leaders, that military dominance without accountability corrodes legitimacy faster than any external enemy ever could.

Critics immediately accused him of undermining national unity, claiming such rhetoric emboldens adversaries and weakens America’s negotiating position during moments of international tension.

Yet that backlash only amplified the post, because Gallego’s credibility as a combat veteran complicates attempts to dismiss his criticism as naïve, unpatriotic, or detached from the realities of conflict.

The controversy grows sharper because Venezuela, unlike past war theaters, does not fit the familiar script of imminent threat, forcing Americans to ask what strategic necessity actually looks like today.

Gallego’s framing rejects the idea that legality and morality are optional luxuries, insisting they are foundational constraints meant to prevent exactly this kind of rapid slide into normalized violence.

Social media reactions reveal a fractured public, with some praising his courage and others accusing him of exploiting his service record to score political points in an already polarized environment.

What makes this moment uniquely volatile is Gallego’s explicit rejection of outcome-based justification, arguing that even a favorable result cannot retroactively legitimize an illegal and unnecessary war.

That position challenges a long-standing American habit of judging wars by whether they appear successful rather than whether they were justified, authorized, or avoidable in the first place.

Veterans’ voices rally behind him, with many sharing stories of conflicts sold as temporary, defensive, or essential, only to metastasize into prolonged commitments with shifting goals.

Opponents counter that global leadership requires decisive action, warning that restraint can be misinterpreted as weakness in an international system increasingly defined by power competition.

Gallego’s post directly confronts that logic, suggesting that unchecked power is not strength but arrogance, and that fear of appearing weak has repeatedly dragged the nation into catastrophic decisions.

The accusation of illegality reopens constitutional wounds, reminding Americans that Congress, not the executive branch alone, is meant to decide when the country goes to war.

This reminder resonates because many voters sense that war-making authority has quietly migrated away from democratic debate into classified briefings and executive justifications few citizens ever see.

Gallego’s message feels incendiary because it strips away euphemism, refusing to dress conflict in humanitarian language or strategic abstraction that distances the public from responsibility.

His critics argue the world is more dangerous now, insisting old rules cannot constrain modern threats, a claim that has historically accompanied nearly every expansion of military authority.

Supporters respond that constant danger is precisely why constraints matter most, not least, because fear has proven to be the most reliable engine of overreach.

The viral spread of Gallego’s post reflects an algorithmic hunger for clarity, especially when that clarity cuts against official messaging and challenges deeply ingrained assumptions about American benevolence.

Younger audiences engage intensely, seeing his words as confirmation that skepticism toward endless war is not ignorance, but a learned response to decades of broken promises.

Older critics warn that such rhetoric risks eroding trust in institutions, though many concede that trust has already been damaged by repeated contradictions between stated values and observed actions.

Gallego’s Iraq War experience looms over the debate, serving as an unspoken warning about how confidently leaders once defended decisions later acknowledged as disastrous.

This historical echo intensifies the discomfort, because it suggests lessons paid for in blood are being sidelined in favor of familiar, convenient narratives.

The central controversy is not whether America can project power, but whether it still believes power must answer to law, consent, and moral restraint.

As the post continues to spread, the argument shifts from Venezuela itself to America’s identity, asking whether dominance has quietly replaced leadership as the nation’s guiding principle.

Gallego’s declaration forces a reckoning with the idea that patriotism may sometimes mean dissent, especially when silence enables actions that contradict foundational democratic values.

Whether his words change policy remains uncertain, but they have already changed the conversation, making it harder to pretend this war is either inevitable or unquestionable.

The most unsettling outcome may be that many Americans, confronted with his clarity, realize the line between protector and bully is thinner than they were ever taught to believe.